An Episcopalian, a Lutheran, and a Congregationalist go into a bar.

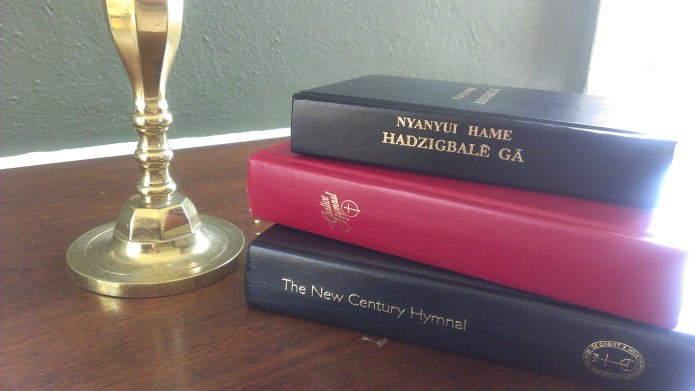

I know this sounds like the start of a joke, but it is actually more or less a true story. Several years ago, my UCC colleague Eric Fistler told me that he and two colleagues were talking together, and they discovered that the three of them shared the same dream, of starting a new sort of church. A church that would worship outdoors, rain or shine, welcoming the homeless as well as the housed. A church that would celebrate weekly communion as it had been celebrated in the early church: as part of a common meal, at which food was freely given and freely shared.

But before the three friends could turn their dream into a reality, there was some planning to do: obtaining the blessing (and financial support) of their respective denominations; coordinating schedules with local food pantries and churches; finding a location and obtaining city permits. Finally Eric gave me a call, inviting me to their first worship service in downtown Northampton. It was January, and bitterly cold; one of the volunteers actually got frost bite that night. But slowly, from that first night, Cathedral in the Night began to grow.

Not long afterwards, I arrived one Sunday afternoon to help set up, only to discover that a small group of folks had already gathered just down the block. They had crockpots of stew, and a box of vegetables, that they were giving away free.

And I have to confess, my first thought was: Uh oh. We have competition.

Who did these guys think they were? So much preparation and thought had gone into our ministry; who were these upstarts who just showed up, without permission or planning, to hand out free food on ‘our’ sidewalk? Most frustrating, they seemed to be accomplishing what we were still struggling to do: they were engaged and connecting with the people on the street.

A few moments later, a young man from the group came over to our table. He looked to be in his early twenties; he had a beard, and wore a long skirt. He introduced himself as Tony, and he said:

“We’re packing up for the day but we have some food left over. Would it be okay if we bring it over here, so you could serve it at your meal?”

And he hurried off, to help fill our table.

I am not the first person to mistake an ally for a competitor; this sort of holy turf war is apparently as old as the church itself. In Mark’s gospel, we find the apostle John telling Jesus: We saw someone casting out demons in your name, but we told him to stop, because he wasn’t actually part of our group.

And Jesus tells them: Don’t stop him! Whoever isn’t against us, is for us.

Most of us know this expression the other way around: If you’re not for me, you’re against me. It’s easy to confound the two expressions, as if they were equivalent. And they would be, if the world were neatly divided into friends and enemies, for and against. But we live in a world of in-betweens and unknowns. What do we do, when we are faced with a new face? Do we operate under an assumption of friendship, or an assumption of conflict?

We don’t know who this stranger was, casting out demons in the name of Jesus. How did he know who Jesus was? Had he heard him preach, or maybe even been healed by him? Why did he strike out on his own, instead of following Jesus?

We don’t know what the stranger was thinking, but we can guess how the disciples must have felt. They had been hand-picked by Jesus, called to be his disciples and walk in his footsteps. And now, suddenly, here is this stranger, casting out demons. And I’ll bet the disciples first thought was:

Uh oh. We have competition.

Who did this guy think he was? Who was this unordained upstart who just showed up, without calling or commission, to heal people in Jesus’ name? Most frustrating, he seemed to be accomplishing what the disciples themselves were still struggling to do.

Why just the other day, a man had brought his son to the disciples, asking them to cast out the demon of epilepsy that was sending the boy into convulsions. The disciples had tried, but they hadn’t been able to cure the boy. In the end, Jesus prayed with the boy’s father, and the boy was healed; but it was discouraging, I’m sure, for the disciples, not to have been the ones to help him.

Deep down inside, we all long to be someone’s savior. We want to be the hero, the one who saves the day – or if not the hero, then at least the hero’s right hand man. If we can’t be Harry Potter, at least we want to be Ron or Hermione, and not just another nameless Hogwarts student. If we can’t be Batman, we at least want to Robin.

That’s actually what the disciples had just been arguing about, as they walked along the road together: which among them was Jesus’ right hand man? Jesus reminds them that they are all servants of the same God. And so for that matter is this stranger they met on the road, the one who was walking his own path, casting out demons as he went.

He’s not the competition, Jesus tells them. He’s an ally.

I wonder if it is human nature, perhaps, to be jealous of another’s success, even – or maybe especially – when we are working for the same goal. In a world of scarce resources and limited opportunities, our future depends on our ability to outperform our peers. We fight not just for market share, but also for promotions, and so we compete — not just against the opposing team, but also against our own teammates.. This is how it is, in the kingdom of this world.

But in the kingdom of God, Jesus tells us, things are different. In the kingdom of this world, we try to climb the ladder; but in the kingdom of God, we help another to rise.

We, of course, live in both worlds. As disciples of Christ, we are called to be in this world, but not of it. That isn’t always easy to do, especially when your personal livelihood gets mixed up with your service to others. It’s hard to be pleased for another’s success, if it means they get the job, or the grant, or the glory.

Or the pledges.

The church, too, lives in this world of scarce resources and limited opportunities. And in an era when church membership in America is declining, it is easy to look upon the church across town as a competitor, instead of an ally. We hear of a thriving youth group or a successful outreach program in another church, and instead of rejoicing, we feel a twinge of envy. Why didn’t we think of that first?

But what if we really believed the words of Jesus, that those who are not against us, are for us. What if we really believed, that we were all servants of one God? What if we really believed, that there was enough grace to go around? God knows, there is enough need to go around. What if we were allies, instead of competitors?

And so an Episcopalian, a Lutheran, and a Congregationalist walk into a bar, and a new ministry is born.

Sometime afterwards, as we were setting up for Cathedral in the Night, some loud singing broke out down the block. Tony and a friend were entertaining the folks at their gathering with some old campfire songs. One of our own visitors came over to me and asked:

So who’s the competition?

That’s not the competition, I told him. Those are allies.

(from a sermon preached by Liza B. Knapp at Belchertown United Church of Christ, October 11, 2015).

(photo: Cathedral in the Night)